AircraftProfilePrints.com - Museum Quality Custom Airctaft Profile Prints

‘The fog of war’ is an often-used phrase, applied most frequently to the confusion that takes place during a battle and how difficult it is for a commander to achieve a ‘God’s-eye view’ of what is happening in all areas of the battlefield in real time. But confusion also applies to strategic considerations – it is unlikely that anyone before 1914 could imagine the Grand Fleet of the Royal Navy, the most powerful and expensive armada the world had ever seen, would only participate in one major battle in four years of war. Few could have predicted how close U-boats would come to choking off vital supplies to the British and few believed that the major European war (which almost all agreed would occur sooner or later) would last beyond a year. So strong was this latter belief that it was not until the bloody battles of Verdun and the Somme had ravaged German, French, and British armies in 1916, that the British Admiralty allowed new design warships to be built: prior to this decision, only vessels already designed could be built or converted. When 1917 opened with the intensive U-boat campaign designed by Germany to knock the British, whose food needs depended upon overseas supply for 50% of the total (1), the need to replace merchant shipping and to built escort vessels was so intense, that there was little room or available labour in the shipyards for new design warships. The year 1916 was a year of great disappointment for the Royal Navy. While the problem of defending the British Isles from Zeppelin bombing raids was never entirely solved, at least by 1916 the RNAS (Royal Navy Air Service) had aircraft that could reach and shoot down the Zeppelins (2) and so that embarrassment of being almost helpless was ended. But 1916 saw the Battle of Jutland where the Grand Fleet was bloodied by the German High Seas Fleet and twice Admiral Scheer [Picture 1] escaped the trap set by British Admiral Jellicoe [Picture 2], in large part because Jellicoe was worried that his fleet was being led towards minefields. The Germans retreated to their protected bases, taking great pride in their gunnery and seamanship but not having accomplished the goal of trapping and destroying a portion of the Grand Fleet. Once this was accomplished, then they could fight an all-out battle on more-or –less even terms: success in such a battle would lead to control of the Atlantic sea lanes and the elimination of Great Britain from the war. Despite Jutland, the British still had the German High Seas fleet confined to the North Sea and still outnumbered the Germans 2 to 1. But that smaller German fleet, a ‘fleet in being’ in naval parlance, in effect was tying down a larger British fleet to its base in Scapa Flow. And then in August, 1916, the German High Seas Fleet set sail again and the British Admiralty, having intercepted and decoded German radio signals, ordered the Grand Fleet to weigh anchor. The chance to destroy the German fleet, to accomplish what had not been accomplished at Jutland, had presented itself. And then that chance evaporated: Zeppelins flying reconnaissance spotted the Grand Fleet and gave warning. The Germans returned to their bases and stayed there for the rest of the war. The Germans, who had gambled in 1914 with the Schlieffen Plan and come so close to Paris they could see the Eiffel Tower, now embarked on their second great gamble. Having resisted the British at the Somme, having failed to break the French at Verdun, and having pushed back the Brusilov offensive on the Russian front, the German army could see no end to the stalemate on land, but at sea an all-out U-boat offensive [picture 3] could knock the British out of the war. Such an offensive would likely lead the Americans to declare war on Germany but its army was small and untrained. The Germans calculated (correctly, as it turned out) that it would take the Americans a full year or more before they could send large numbers of trained and equipped soldiers overseas – before then, however, the British would be starved into making peace, and that would force the French and Russians to come to terms favourable to Germany. And the German High Seas Fleet? So much scrap metal whose only purpose now would be to tie down the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet – every escort ship at Scapa Flow was one less to fight the U-boats.

The year 1917 was perhaps the most desperate year for the Allied forces, punctuated by disaster after disaster. The British were sent reeling by the intensity of the U-boat campaign (and the United States’ declaration of war on April 4, 1917, while psychologically valuable, provided no immediate relief); the French armies suffered mutinies throughout the spring and summer; a revolution occurred in Russia in March which led to further demoralization of Russian forces; and in October at Caporetto, a combined German-Austrian force rolled over the Italians and were pushing towards Venice before Italian resistance stiffened and then held. But the greatest disaster was the Bolshevik Revolution for Lenin [picture 4] and his comrades were determined to take Russia out of the war. On Dec.2, 1917 the Russians and Germans signed an armistice and the Germans swiftly sent forces to occupy Ukraine. The Russians were in no position to resist (3). Having seized the Ukraine breadbasket and having knocked out the largest army opposing them, the Germans were tempted to believe that the war was over. The Allied blockade, represented by the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, no longer could be effective (4), and if necessary German forces on land could hold off the British and French for years. Further fighting on the Western Front would be pointless. In January, 1918, the Germans sent out peace feelers – and were rejected by the British [Lloyd George – picture 5] and the French [picture 6 --Georges Clémenceau]. Woodrow Wilson [picture 7] of the United States issued his ‘Fourteen Points for Peace’ in this month but once he had seen the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that Germany imposed on Russia, he is reported to have said “We cannot deal with these people”. Now the German problem was a repeat of 1914: the need to knock out the British and French armies before a third large force (this time the Americans) made its presence felt. And so, the final German gamble, pulling all its troops from the East and launching a final all-out assault in the West to capture Paris. The U-boat campaign of 1917 had almost succeeded: from March to June, 1918 the Germans again came close enough that the Kaiser was invited to near the front line, a position from which he could see the Eiffel Tower. But the Allied line did not break and in July they began regaining ground. By August, the trench line that had been established back in October, 1914 was broken and the German army was steadily pushed back, its retreat ending only with the Armistice on November 11. And what was the Royal Navy doing in 1918? It was planning to use a mythical beast called the Argus and a little bird called the Cuckoo.

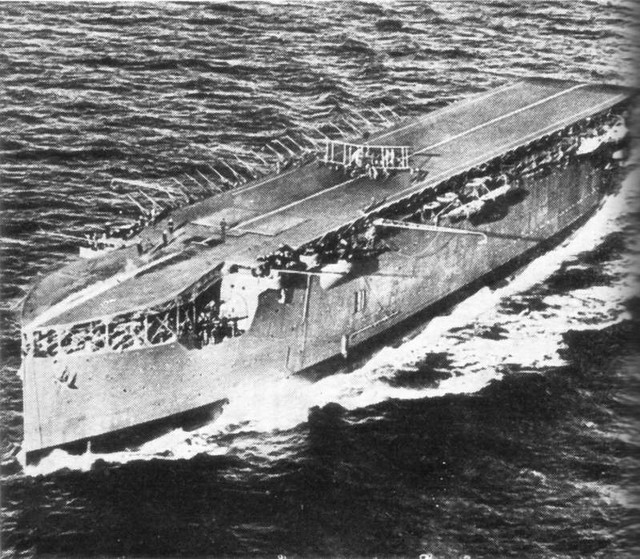

HMS Argus joined the Fleet in September, 1918. She was beginning to get her crew worked up to be an effective ship and to begin offensive operations as soon as possible. Admirals Beatty[picture 8] and Jellicoe could hardly wait to put the ship and its aircraft into action for Argus appeared to have solved the problems involved in landing on a ship at sea, a problem that could not be solved by the partial ‘flying-on decks’ installed on HMS Furious and HMS Vindictive. Then came the Armistice and Argus never did launch any strikes against the German High Seas Fleet. Strangely, within a few short years the Admiralty would be quite willing to scrap its ‘hundred-eyed giant’ (mythological origin of Argus’ name) to gain tonnage as defined in the Washington Treaty of 1922, yet circumstances worked in such a way that she served almost continuously with the Fleet to near the end of WWII, and although she had long since been designated as a training ship, she nevertheless undertook combat patrols at different times during the later war (5). HMS Argus began life as a liner to be built by Beardmore Shipyards for the Italian Lloyd Sabaudo Line as the Conte Rosso. She had a sister ship, Hull 967, at the Swan Hunter yards (to have been named Giulio Cesare). Both of these cargo-liners had been ordered in 1914 but when war broke out, work on them was suspended. Hull 967 was further along in construction than the Conte Rosso but the propulsion machinery of the Beardmore hull was almost complete and as this machinery was the ‘controlling bottleneck’(6) it was chosen in September, 1916, to be completed as an aircraft carrier(7). The yard promised to have the conversion completed by late 1917 but in the event the ship wasn’t ready until the autumn of 1918: much re-thinking of the design took place while the vessel was under construction. The person chiefly responsible for design considerations was J.H.Narbeth, Assistant Director of Naval Construction. It must be remembered that Narbeth, the Admiralty, the aircraft manufacturers, and the pilots were all entering uncharted territory – everything learned by the pilots, for example, would impact on aircraft design and construction, on the design of the ship, and on tactical considerations in creating exercises and actual operations. HMS Argus, as completed, was 565’ overall length, 68’ at the beam , with a mean draught of 21’ (172m x 20.7m x 6.4m); she had four shafts and her 15,000 tons [picture 9]could make a maximum speed of 20.5 knots, somewhat slow for work with the Grand Fleet but her expected accommodation of 20 aircraft was a great improvement over anything previously existing. Provided, of course, that one could actually land, safely and regularly, on a moving ship – and as Argus was being built, that problem had yet to be solved.

Experience with the early seaplane carriers convinced the Royal Navy that the less time an aircraft spent on an exposed flight deck the better: it was difficult to hold down the light airframes of WWI, particularly when as biplanes they had such extensive lifting areas. Land, get the craft quickly to a lift, and move the aircraft into the hangar away from the elements. This thinking determined one design feature of all British carriers up to and including the Colossus and Illustrious classes of WWII; namely, that the size of a carrier’s air wing was determined by the capacity of its hangar(8). In the case of HMS Argus, its hangar of 350’ x 68’maximum (106.6m x 20.7m) allowed room for 20 aircraft [picture 10]. This hangar deck, as with all British carriers up to WWII, was the strength deck. A light flight deck was built above the roof of the hangar deck on a steel web framework and the space in between was used for the ‘tunnel funnels’ that brought exhaust gases from midships to be released at the aft end of the ship, still below the flight deck[picture 11]. The original design had two features that were dropped during construction. The first was a stern slipway for seaplane recovery (remember: it is still 1916 and seaplanes for all their weaknesses were available in large numbers) but it was abandoned (9). The other feature was the presence of port and starboard ‘deckhouses’ (what we today call ‘islands’ or ‘superstructures’) connected together by a navigating bridge high above the flight deck. This scheme had been proposed in 1915 for one of the seaplane carrier conversions. A further feature was to suspend a crash barrier, similar to the one in HMS Furious, between the two islands. But wind tunnel tests done at the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington in November, 1916, showed that these structures seriously affected airflow over the flight deck. The landing experiments later done on Furious confirmed these unhappy results. Putting the bridge, funnels, masts and spotting nests all to one side of the ship had been proposed by Flight Commander Hugh Williamson and in crude model form shown to Narbeth in September, 1915. Narbeth did not adopt the idea for Argus (although he was soon to put island superstructures into Hermes and Eagle whose construction were only a few months to a year behind Argus)(10). Superstructures made the problem of removing combustion gases so much simpler than the trunking required in Argus as built (and later Furious). Argus emerged as a ‘flush-deck’ carrier, the navigation function being taken care of by a retractable pilothouse-charthouse that was lowered flush with the flight deck for flying operations. [pictures 12 and 13]. Once launched, however, Argus was provided with a large dummy island superstructure (11) and landing tests occurred in October, 1918. These demonstrated that the island did not significantly restrict or affect pilots on landing and even aided landings by providing a height off the deck reference (no Landing Signals Officers existed at this time). As it turned out, only Argus and Furious would be built without islands: all other British carriers would have one on the starboard side, a practice followed (with only two exceptions) by all other carriers built by all other nations.

Once the dummy island was removed, Argus took aboard the first of its new Sopwith torpedo bombers, the T.1, named ‘Cuckoos’(12)[picture 14]. Sopwith had produced the Baby [pictures 15, 16, and 17],the 2F.1 Camel [picture 18], the Pup [picture 19], and the 1½ Strutter [picture 20]—all used aboard various ships of the Royal Navy during the war, but the Cuckoo was purposefully designed to carry an 18 inch torpedo which had twice the explosive charge of the earlier 14 inch. Argus and her aircraft were expected to go into battle, attacking the German High Seas Fleet in port. Once the Germans realized there was no safety in port, they would have to bring out their ships in order to gain manouevring space, if nothing else. Once out of port, they could then be destroyed by the Grand Fleet. Aircraft launched by catapult from battleships and cruisers, and from Furious and Vindictive could shoot down any Zeppelins that made an appearance and could keep up almost continuous reconnaissance above the German fleet because now, rather than ditching, they could land on Argus, hopefully to be refueled and take off again. Such were the hopes of the Admiralty as the Cuckoos were delivered and her pilots and mechanics came aboard Argus and the ship’s crew began work-ups to make the ship operational. At first, aircraft landed on a bare deck but soon the system of longitudinal wires that had been on Furious was installed. Experiments showed that it had been installed too far forward but moving the system towards the stern meant covering up the rear lift (which, in any event, was not operable in the fall of 1918 – the Admiralty wanted Argus, which took a year longer to get into the water than originally promised, as soon as possible). That rear lift was lowered 18”(45cm) with ramps covering the ‘steps’ that this made: this configuration was seen as helping to slow the aircraft down and helping it to engage the wires that would keep its path straight(13). Consider the problem: a wood and canvas aircraft with two wings is trying to set itself down on a moving ship. If it approaches too slowly, it loses rudder effectiveness and cannot make corrections. Too fast in the approach and it will float over the deck: if a quick downward motion is initiated by the pilot, the likely result will be a bounce-back into the air (and perhaps structural damage as the aircraft of 1918 did not have shock absorbers). Once the aircraft was on the deck, members of the ship’s crew would run out to grab the wings to slow it down (again, these aircraft had no brakes), push it to the forward lift, take it down to the hangar, push it off the lift, and then ride the lift back up to the flight deck to be ready for the next aircraft to land (14). Once pilots and deck crew were fully trained, one aircraft per minute could be taken aboard but Argus and her crew had not reached this level of proficiency when the Armistice occurred and the fighting stopped (15). The war had ended but meanwhile tests continued aboard Argus as it was the only full deck carrier the Royal Navy had. The single greatest problem encountered was keeping the aircraft flying straight both as it approached the deck and when landing. Transverse ropes had been tried as long ago as 1911 but they were never part of the ship’s structure: rather, they were rigged when necessary and weighted with sandbags to provide resistance. Once a particular rope (not wires: these aircraft were wood and canvas and easily damaged) was caught, it would be pulled out of position, fouling other ropes and the next aircraft could not land until the ropes were put back into place. If an aircraft did not hit the transverse rope exactly at centre, then it would slew to one side and was in danger of falling off the flight deck into the sea. Transverse ropes tested on land in 1916 fell out of favour and so the longitudinal system was installed on British carriers. It too had its problems and would be removed by 1927(16). Not until 1933 would a system of transverse wires, adopted from the Americans, be installed on British carriers. The light aircraft of WWI and the 1920’s did not have good slow-speed qualities when in a tailwind, thus the early carriers, beginning with Argus, had to turn into the wind not only for take-offs but also for landings. All was well if the wind was steady, but any gusting and an approaching aircraft would bounce up and down and since Argus’ funnel gases discharged directly under the extreme end of the flight deck, this problem was even more pronounced (17). Pilots, properly fearing hitting the stern of the ship, or even having their wheels sheer off, demanded a ‘round-down’ or curve on the extreme end of the flight deck. This was done on British carriers but Argus had only a very modest curve to the end of her flight deck[pictures 21 and 22]. A greater problem than fear of hitting the stern was having one wing tipped by a wind gust just as the aircraft passed over the stern – slow speed and this loss of directional control with little or no time for a pilot to respond usually meant an accident and damage to the aircraft, although the pilots tended to be only shaken up rather than seriously injured. In trials with Argus in 1919 it was shown that if the ship turned 10 degrees off the wind, the current rushing up the one side of the ship was strong enough to throw an approaching aircraft clear off the deck, no matter how hard the pilot fought the controls (18). Only 5 degrees or less of wind off the centerline was considered safe. In turn, that required that the ship have good sailing qualities to keep her head into the wind in rough seas. And in rough seas the ship would roll and pitch. Landings were made during tests in the Orkney Islands area with the ship rolling up to 5 degrees and pitching 2 or 3 degrees. A double roll in Argus took 12 seconds and on the pitch axis about 8½ seconds, so a pilot on the approach saw several ship movements and adjusted as best he could (again, no LSO existed). One lesson learned from all these tests was that the larger the ship, the better sea-keeping qualities it would have, and thus smoother flight operations could be expected (19). Then again, a larger ship would be more expensive.

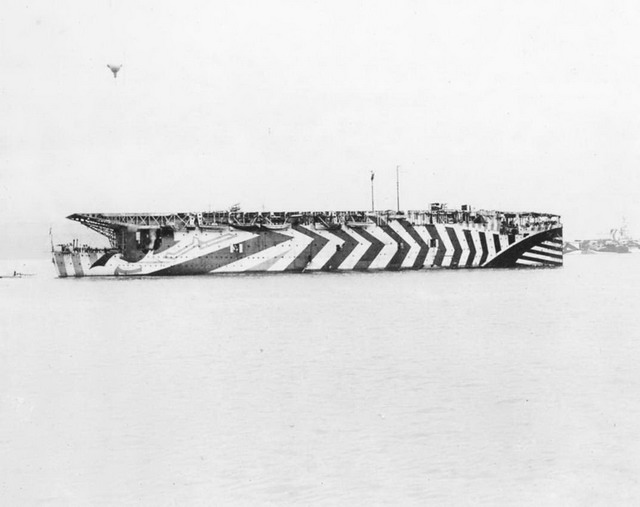

Some features of Argus, such as the armoured hangar, remained standard in British carriers; others, such as the lack of a superstructure, did not. And further features were adopted by the first generation of carriers (Hermes and Eagle) but not continued in later ships. The most noticeable feature to be discarded was the coming to a point of the flight deck at the bow: it was found that any squaring off of the forward flight deck (still called the ‘flying-off deck’ in 1919) produced an ‘air bump’ that planes had to be launched through. The later carriers (re-built Furious, and her half-sisters Courageous and Glorious) had a ‘round-down’ at the forward end of the flight deck as well as at the stern(20). The forward air ‘bump’ was not as severe in these ships and from the late 1920’s onward, the aircraft were not as fragile as the early machines of 1917-23. Finally, the one feature that distinguished Argus from all other carriers, was her distinctive ‘dazzle’ camouflage [pictures 23, 24, and 25]. The Admiralty came to believe that these schemes made ships more obvious and easier to spot and were not worth the considerable labour involved(21). And the Admiralty, stuck with severely restricted finances with the onset of peace, was more than willing to scrap Argus as soon as possible so long as she could be replaced by a new warship. Note the emphasis on ‘warship’ for of all the carriers the British would operate between 1918 and the arrival of the Ark Royal in 1938, only Argus did not begin life as a warship. She was a converted liner, slow at 18kts (although she made 20.5 on her trials), and heeled with only a 5 degree rudder deflection. She was ‘girdled’ with a 3 foot thick, 19-foot high belt of wood in 1926 to improve her stability and at the same time, new radio masts and guns were installed (22). Her hull, when inspected in 1927, was found to be quite strong and able to give another 15 years of service(23). But it was not the hull of a warship and thus front-line service was out of the question. She was laid up in reserve, May, 1930, but brought back as a mother ship for target practice and as a training carrier in 1938. The loss of three large carriers early in WWII (Courageous, Glorious, and Ark Royal) forced Argus into front-line service during the hunt for the Bismarck in 1941 and in support of Allied landings in North Africa in 1942 (24). As more carriers were produced in British and American yards, the pressure eased and she was put in reserve again late in 1943 and then turned into an accommodations ship in August, 1944. She was scrapped in 1947. Only carriers with service lives stretching 40 years or more (such as USS Midway, CV-41, or USS Enterprise, CVN-65) can come close to matching Argus’ record of having been home to 44 different types of aircraft (25).

Once again a ship that deserved to be modeled has been slighted. Once again, Navis and Neptun, makers of 1:1250 ships in metal, have rendered Argus both as she was in 1918 and in 1941 (26). But I could find no plans on any website (27), nor any kits, be they plastic or resin. What was found, however, was a beautiful model on the Premier Ship Models website (www.premiershipmodels.com). Eleven pictures of this model [pictures 26-36] are shown here with the kind permission of Premier Ship Models. These pictures certainly provide an eye-catching, eye-pleasing contrast to the black-and-white pictures normally found and used earlier in this article. In scanning the web, I found a 36” radio-controlled model of Argus that was built by Ashley Needham: it was inspired by a model of the Argus that he viewed in the National Maritime Museum in London (28). Next: HMS Hermes and HMS Eagle

1. Besides food, one item had a particular strategic value: lumber from Canada. Britain had all the iron ore and coal it needed to make as much steel as necessary; however, wartime demand was so great that the coal-mining galleries underground had to be rapidly expanded and these galleries required ever-increasing amount of large, squared timbers (‘pit-props’) to keep from collapsing. 2. British fighter successes forced the development of ‘high flyer’ Zeppelins which could reach altitudes of 5,000 metres or higher: but time at this altitude was limited, just as a U-boat’s endurance was limited, by available oxygen. ‘High-flying’ appears to have been an escape tactic rather than a regular operational feature. 3. In Lenin’s words “Militarily, we are a zero”. The war was unpopular, and the Bolsheviks, with their “Peace, Land, Bread!” slogan all through 1917 tried to stir up mutinies and demoralize the army. They succeeded too well and by being forced to sign the disasterous Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March, 1918, merely exchanged one war (against the Germans) for another (the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922). 4. Germany’s strategic and food requirements were not as constricted as the British but the blockade began to have its effects: the winter of 1917-18 was known as the ‘turnip winter’ as people, not livestock which had mostly been consumed, now ate the vegetable. 5. In this respect her career was like that of Japan’s first carrier, Hosho. 6. Friedman, N., British Carrier Aviation: the Evolution of the Ships and their Aircraft, Conway Maritime Press, 1988, p.47 7. The request had originally come from Jellicoe a few weeks before Jutland for air-capable ships that could supply the fleet with continuous reconnaissance. 8. In order to provide a larger air wing, the British would develop on some of its carriers a double hangar, to be discussed in more detail in later articles. 9. Layman, R.D., Before the Aircraft Carrier: the Development of Aviation Vessels: 1849-1922, Conway Maritime Press, 1989, p.69. The same feature was part of HMS Hermes original specifications. 10. Ibid., pp.69-70 11. Friedman, op. cit., p.67. Made of wood and canvas it was easily assembled and dismantled. It was meant to imitate the island proposed for HMS Eagle, then building, and was provided with a smoke generator to imitate funnel gasses. 12. Preston, Anthony, Aircraft Carriers, Galahad Books, 1979, p. 22. “The name Cuckoo was a whimsical reference to its ability to ‘lay eggs in other people’s nests’”. 13. Layman, op. cit., p.71 14. A rhythm not achieved until the late 1920’s-early 1930’s. Beaver, Paul, The British Aircraft Carrier, 3rd ed., Patrick Stevens Ltd., 1987, p. 27 15. So the dream of destroying a fleet in its own port had to wait until November, 1940 when Admiral A.B.Cunningham’s Swordfish from the carrier Illustrious crippled major units of the Italian fleet at Taranto. This attack, in turn, inspired the Japanese to plan and execute the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. 16. “Palisades” would be installed on the sides of the ships to prevent aircraft from falling off the flight deck. This will be discussed further in a later article. 17. Captain Mortimer Neame approached Argus as she made 12 knots into a 20kt wind and hit an air bump that forced his aircraft down: the wheels hit the round-down and slowed the aircraft so much that 28. found at www.modelboats.co.uk/albums/member_photo.asp?a=4288p=2683 the engine stalled, and the plane rolled backwards and crashed onto the quarter deck. There being no island on Argus, no one on the bridge saw what happened and assumed the worst. Neame, unhurt, would later command the carrier Vengeance in WWII. Beaver, op.cit., p.15 18. Friedman, op.cit., p. 79 19. Ibid., pp.80-81 20. Ibid. p.79 21. Based on patterns proposed by marine artist Norman Wilkinson. The design was meant to confuse range-takers who in WWI relied on optical equipment. Hobbs, D., Aircraft Carriers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies, Greenhill Books, 1996, p.22. Colour pictures of this scheme are seen in the modeling section of this article. 22. Friedman, op. cit., p.67 23. Ibid., p.69 24. In this Argus was like her near-contemporary, IJN’s Hosho, suffering damage (Nov.10, Operation Torch) but surviving the war. Layman, op. cit., p. 72 25. Idem 26. Navis – 180N (Argus in 1918); Neptun 1125 (Argus in 1941) 27. If you know of any plans that are easily available (writing to the National Maritime Museum is not likely to be simple or cheap) then let this author or the website manager know: one of the projects for the far future will be a master list of all kits and plans for every carrier/carrier class.

Beaver, Paul, The British Aircraft Carrier, 3rd ed., Patrick Stevens Ltd., 1987 Friedman, Norman, British Carrier Aviation: the Evolution of the Ships and their Aircraft, Conway Maritime Press, 1988 Hobbs, D., Aircraft Carriers of the Royal and Commonwealth Navies, Greenhill Books, 1996 Layman, R.D., Before the Aircraft Carrier: the Development of Aviation Vessels: 1849-1922, Conway Maritime Press, 1989 Preston, Anthony, Aircraft Carriers, Galahad Books, 1979

1. Fontispiece of the 1920 book Germany’s High Sea Fleet in the World War (public domain) 2. U.S. Library of Congress, Bain Collection, ggbain.38732 (public domain) 3. From a postcard sent in 1917; painting done in 1917 by Willy Stöwer (1864-1931) (public domain) 4. public domain (Lenin) 5. U.S. Library of Congress cph.3a10674 6. public domain; scanned from a PD book at www.gwpda.org/photos/bin14/image1396jpg 7. U.S. Library of Congress cph.3f06247 8. public domain; source: http://www.firstworldwar.com/photo/graphics/Nw_beatty_01.jpg 9. from Ships of the World, op. cit., p.33 10. source unknown; shows hangar deck in 1943 11. adapted from Friedman, op.cit., p.70 12. USNHCC photo # NH 42235 (1918) 13. USNHCC photo # NH 63028 (1920’s) 14. from www.aviastar.org/air/england/sopwith_cuckoo.php ; in the public domain 15. The Pioneers: An Anthology: Sir Thomas O.M. Sopwith; http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au 16. Idem 17. Idem 18. Idem 19. Idem 20. Idem 21. IWM, public domain 22. IWM, public domain 23. USNHCC photo# NH 42235 24. USNHCC photo# NH 63225 25. USNHCC photo# NH 63030 26 – 36. By permission of Premier Ship Models

Photos and text © 2010 by Dan Linton January 25, 2010 |