AircraftProfilePrints.com - Museum Quality Custom Airctaft Profile Prints

As has been often repeated in the first four parts of this series, the dream of the Royal navy was to launch a massive strike of torpedo-carrying aircraft from ships – aircraft carriers – that could both launch and recover aircraft, then refuel and re-arm them to strike again and drive the German High Seas Fleet out of their protected harbours. Britain’s main naval allies, the United States, Japan, and France, watched British developments with keen interest and with an eye to copying, matching, or even surpassing what the British had accomplished. Yet by the end of the war, what had the British actually done? HMS Argus was commissioned (picture 1) but had not had her crews worked up to be an effective unit. HMS Hermes (picture 2) and HMS Eagle (picture 3) were within a year of completion but once the war ended, the completions were long delayed. The problem of dispersing stack gases seemed resolved with the acceptance of a starboard island and superstructure; the problem of regularly and safely landing an aircraft aboard a moving ship seemed resolved; and the issues involved in determining the best tactical uses of these new ships and their aircraft held tantalizing promises of making the carrier an essential, not just an auxiliary, part of a nation’s battle fleet. So great was this promise that as early as July, 1920, the United States Navy (USN) proposed to lay down four carriers in three years, despite not having ever built a carrier, either converted or new-built! (1) The USN’s faith in the value of carriers came from an unexpected source: the games played at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island (picture 4). These games formed the framework for the exercises (called ‘Fleet Problems’, beginning in 1920) by which USN carrier aviation would develop into the most advanced in the world, a position it would never relinquish (2). Back in 1919, however, with the war recently ended, the enthusiasm for carriers, strong in some circles in the USN, had not transferred itself to the United States Congress. Capt. Thomas T. Craven in May 1919 was the Director of Naval Aviation and tried to get two colliers, USS Jupiter (picture 5) and her sister ship USS Jason, converted into aircraft carriers. On July 11, 1919, Congress only allowed for the converting of the Jupiter (3). In the next year, Congress refused any funding for more carriers. But then events were to take place in 1921 which would lead the United States Congress to order the largest aircraft carriers the world would see until 1944 (4).

When Congress denied funding for new-build carriers, the search began for hulls that might be converted. It was realized that as useful as the Jupiter conversion might be, a large deck ship would ultimately be necessary. Indeed, British Naval Constructor Stanley Goodall, seconded late in 1917 to the USN’s Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuCon), was listened to with great respect. He had brought with him the preliminary design for HMS Hermes and was asked to comment on each new design proposal that came out of Bucon. He insisted upon a ship at least 800’ long (254m) with a minimum speed of 30kts (5). Indeed, the growth in the size of the ‘new’ carrier in these design studies was continuous until it was realized that it was approaching that of the huge new battle cruisers that were laid down in 1920 (6)(Picture 6). There were other candidates. The ‘Omaha class’ cruisers were under construction (picture 7) and while they would be considerably faster than the Jupiter conversion, now officially named USS Langley (7), they would be no larger. Three liners seized from Germany – Von Steuben, Agamemnon, and Leviathan (pictures 8,9,and 10) – would provide size but their conversion costs would be very high and they were not warships, thus protection against bomb, mines, and torpedoes would not exist. And besides, these ships had been championed by a man who would spend 1920 and 1921 sending ‘poisoned pills’ to the U.S. Navy. That man was Billy Mitchell (picture 11), a zealous convert to the theories of Gulio Douhet and a man whose ultimate objective was the creation of a separate United States Air Force (8). Before Congress and in the press Mitchell urged “….the conversion of three liners…. into aircraft carriers, each dedicated to a different kind of aircraft—fighter, bomber, and attack. He proposed that they form a separate naval squadron, not under fleet command. This independence from Navy control was to be ensured by the fact that funding for the conversions and for the aircraft that flew off their decks would be from the Army’s budget” (9). No sooner had the Navy finished explaining to Congress and the public why the liners were inadequate then Mitchell staged the famous bombing trials with Army bombers attacking naval vessels (picture 12), ultimately sinking the modern German battleship Ostfriesland in July, 1921 (picture 13). The publicity from these tests, and the acrimony that developed between the Army and Navy (picture 14) had a number of interesting consequences (10), one of which was the appointment in August 1921 of Rear Admiral William Moffett as the first chief of the newly formed Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer).

Moffett’s first task was to dampen down the bitterness that Mitchell had caused both between the Army and the Navy, and in Congress. In this he was helped both by his own calm demeanour (picture 15, above) and by the fact that Mitchell was so zealous and abrasive that he was court-martialled in 1925 and resigned from the Army in 1926. As regards naval aviation, Moffett had no doubts about its value and future and he set about to make it an integral part of the service – the planes that flew from Navy ships would be ordered, owned, and operated by the USN. He “….made aviation a part of the staff structure….navy pilots were on the same career track as other naval officers, with the goal of commanding ships and fleets eventually. They were naval officers first, pilots second. This close connection was exemplified in 1941 when Admiral Ernest King, a pilot, became Chief of Naval Operations.”(11) Moffett also had support from a group usually thought to be hostile to (or at least in competition with) naval aviation – the so-called ‘Battleship Admirals’. Tests conducted with the USS Texas (picture 16) in March 1919 using aircraft for gunnery spotting showed a significantly improved accuracy: command of the air over a naval encounter was thus seen as essential and as seaplanes had obvious limitations, then carriers were to be welcomed as part of the main fleet (12). At the time that Langley, Lexington, and Saratoga wee ordered, the concept of an aircraft carrier as an independent strike unit had not developed, so friction with the ‘Battleship Admirals’ was minimal or non-existent. And Moffett, too old to take a pilot’s course, did take the observer’s course (13). In 1925 Moffett wrote “The Navy is the first line of offense and naval aviation as an advance guard of this first line must deliver the brunt of the attack….naval aviation cannot take the offensive from the shore: it must go to sea on the back of the fleet….The fleet and naval aviation are one and inseparable.”(14) A bold statement – contradicting Mitchell – considering that in 1925 naval aviation was a collection of floatplanes and one small carrier operating only twelve planes. (15) But that was to soon change.

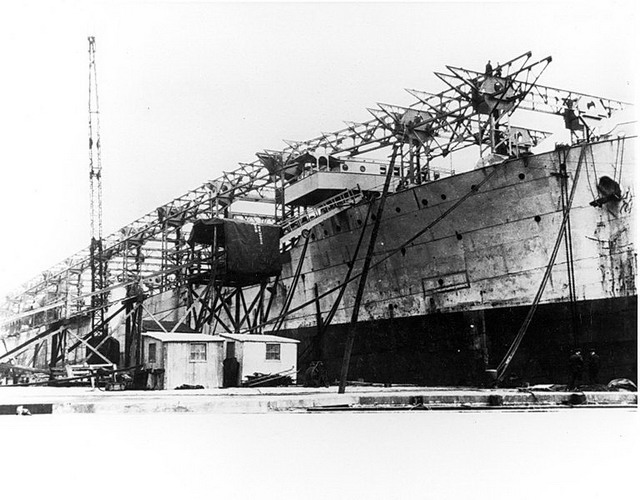

The USS Langley, the USN’s first aircraft carrier, began life as AC-3 USS Jupiter, a large collier. She was chosen for conversion because of her large holds, her turbine-electric drive (16), and because the USN had converted to oil. The recommendation to convert Jupiter came from the Director of Naval Aviation Captain Thomas B. Craven in May, 1919. (17) Jupiter had six deep holds and once the coal-moving gear was removed these were available for avgas (first hold); as hangars for dismantled aircraft (2nd, 3rd, 5th, and 6th holds); and for ordinance (4th hold). (18) The conversion was to have been completed by January 1921 but in fact Langley was not commissioned until March, 1922. (picture 17, above) “The Langley had no hangar deck in the modern sense, as aircraft were not stowed ready for flight. Rather, they were assembled on the former collier’s upper deck, loaded onto an elevator (which in its ‘down’ position stood 8 feet above that deck) and then hoisted onto the flight deck. A former Langley pilot recalled that it took 12 minutes to get an airplane off the elevator and onto the former main deck for disassembly.” (19) (Picture 18) The various struts and girders that supported Langley’s flight deck gave her a distinctive appearance that gave rise to the ‘Covered Wagon’ nickname. (picture 19) These girders also supported the travelling cranes beneath the flight deck that moved aircraft on and off the elevator. (20) (picture 20) She had two cranes to lift floatplanes from the water; a palisade on the forward part of the flight deck to act as a wind-break (picture 21); a top speed of only 14 knots, her 12,000 ton hull being pushed along by two screws. (21) (picture 22). Despite the fact that her fire rooms were well aft, ‘....the chief problem in Langley’s design was smoke dispersal. She had a flush deck with a short folding funnel to port and a smoke opening below the flight deck level to starboard. In theory, either opening could be used depending upon the wind. The starboard opening had special water sprays for cooling, but even so it was not particularly successful and within a short time Langley had been refitted with a pair of hinged funnels to port . (22) (pictures 23 and 24) With a flight deck of 534’ x 64’ she was essentially the same size as her contemporaries, HMS Argus and IJN Hosho, and was expected to operate 12 aircraft. (picture 25) She was a ship to conduct experiments with and what happened on her deck in the mid-1920’s pushed the United States Navy into naval aviation leadership by the 1930’s and earned Langley, once called ‘this poor comic ship’ by one of her first crew members, a place in history

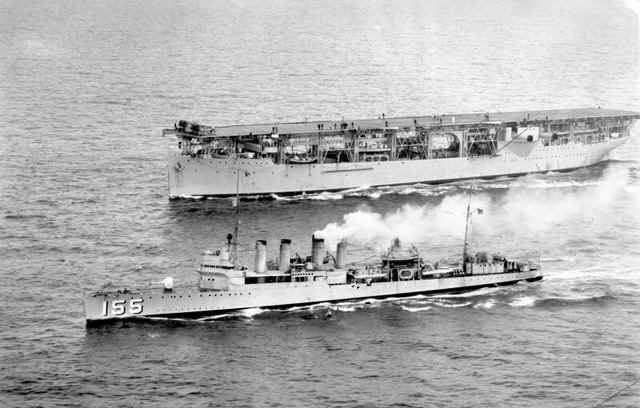

USS Langley was commissioned 20 March 1922. It spent the spring and summer of that year in work-ups and it wasn’t until 17 October of 1922 that Lieutenant Virgil C. Griffen, flying a VE-7, made the first take-off from her deck.(picture 26, above) One week later, 26 October, Lt.Cdr. Godrey de Chevalier made the first landing. (23) (picture 27) On November 18, Cdr. Kenneth Whiting made the first catapult launch from Langley’s deck. Handling of aircraft in larger numbers began in early 1923 using Aeromarine aircraft in groups of three. It was found that it took two minutes to prepare the deck for landing and that the best time to land three aircraft was seven minutes (24)(picture 28) In part, this was due to crew inexperience and in part to the set-up of Langley’s arresting gear. “When Langley was being converted, a reserve lieutenant Alfred ‘Mel’ Pride was....given the assignment of developing a practical arrestor gear. The system he developed was a variant of the then-current RN system, the so-called ‘Busteed Trap’. The Busteed system used a pair of ramps and longitudinal wires....Pride kept the longitudinal wires and small vertical hooks, to keep the plane straight, but discarded the ramps. Instead he developed the tailhook and a set of lateral wires (pendants) to stop the aircraft....Each wire was connected by pulley to a weight hanging from a tower: as the wire stretched out, the weight went up and the aircraft was slowed.... Langley was completed with the original Pride system with towers, but within a year the system had been re-designed to do away with the towers, the weights hanging into the hold.” (25) Nevertheless, accidents happened and Lt. Pennoyer had the distinction of being the first pilot to lose a plane over the side of the ship. He survived to fly again. Only three landings qualified you as a carrier pilot and unlike the situation in the Royal Navy, there was a certain ‘cachet’ to being a carrier pilot in the USN from the very beginning.(26) Langley would move from the waters around Virginia and Florida to the Pacific early in 1925 but before this move an interesting development occurred – in a very unplanned manner – that was to affect carrier operations and make landings safer. The story sounds made-up but is apparently true. “The business of using arm signals to show whether the pilot was high or low or fast or slow came about in an interesting way. The executive officer (of Langley) was Commander Kenneth Whiting....He used to stand in the netting all the way aft on the port side. That was a good place to see what was going on. We had one pilot who had not landed on the deck before.... This chap came in, and apparently, he was very reluctant to actually set his plane down. He kept coming in high, then he’d give her the gas before he quite got to the deck, and go around again. This happened several times. Whiting jumped up and grabbed the white hats from two bluejackets....and held them up to indicate this character was too high. Then he put them down. He coached the fellow in, and that seemed like a good idea. So from then on, an officer was stationed there with flags to signal whether the plane was too high or coming in too fast or too slow”. (27) An thus was born on the deck of USS Langley the LSO. (28) (pictures 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 and 34)

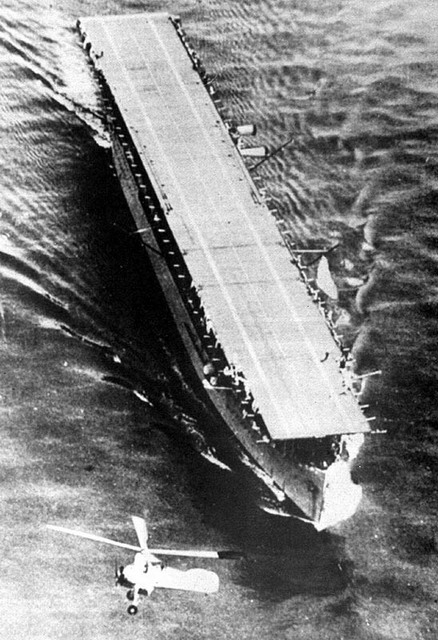

On January 22, 1925 in her new home port of San Diego, California (29), Langley received her first operational squadron (VF-2) (picture 35); joined the battle fleet as a combatant; and participated in Fleet Problem V, beginning March 2 (picture 36). The effectiveness of her scouting so impressed Fleet Admiral Robert Coontz that he urged the rapid completion of the conversions of Lexington and Saratoga. (30) And this was at a time when Langley was still operating only about a dozen aircraft. But all this was soon to change for in October, 1925 Commodore Joseph Mason “Bull” Reeves became Commander Aircraft Squadron, Battle Fleet.(picture 37) Reeves, already a long-serving career officer, attended the Naval War College in 1923-24, served a year in a staff position, and then volunteered for aviation duty at Naval Air Station Pensacola. Like Moffett before him, Reeves qualified as a Naval Aviation Observer, the minimum requirement for holding an aviation command. He was 53. No doubt he was impressed by the idea, floating around in the War College in 1923, of using carriers to strike the Panama Canal (31), but this could hardly be accomplished with a vessel holding only 12 aircraft (picture 38). Reeves insisted that Langley could operate far more than a dozen aircraft. He was a ‘hard driver’ (32) and knew the ship well: he had been the Jupiter’s first captain when it was originally commissioned in 1913. Soon Langley was operating 24 aircraft, then 36, and finally an incredible 42 aircraft, such numbers made possible by the development of the ‘deck-park’, the crash barrier, deck crews drilled hard to push down launch and recovery times and push up sortie rates (33) (picture 39) As an aircraft approached Langley, a set of wires at mid-ships was lifted up to form a barrier: an aircraft that missed all the wires would be stopped by the barrier. Damage to the plane and pilot tended to be minor. A plane that caught the wire would be unhooked, the barrier would come down and lie flat, the plane would be pushed forward and parked on the deck near the bow while the barrier was raised ready for the next plane to come in for a landing. After all the planes were recovered, they would be pushed and ‘re-spotted’ on the flight deck aft and made ready for the next launch: planes requiring repair would be taken below and repaired aircraft brought back up. On such a small deck as Langley’s, this meant that the dangers increased for both pilots and deck crew. “The US Navy, heavily influenced by British WWI experience, initially followed British practice so that the US prototype carrier, Langley, was initially assigned only about a dozen aircraft. In 1926, her commander, then captain JM Reeves, insisted that she could carry and operate 3 ½ times as many....Reeve’s insistence on very quick operations led directly to the institution of the deck park and the crash barrier....the pilots on the Langley, well aware that the innovations were extremely dangerous, opposed them. Reeves succeeded because the aviators on the Langley were directly and unambiguously subordinate to him”. (34) And it was thanks to Moffett’s reforms in 1921 that allowed Reeves to be the ‘hard driver’ that he was. (picture 40) A December 13, 1926 exercise in ‘light bombing’ (soon to be called ‘dive-bombing’) scored 19 hits out of 45 but Reeves was still not satisfied and his aviators, who he scolded for lacking insight, spent Christmas with Reeves’ demand to solve the problem of ‘how can we bomb effectively’? (35) Part of the answer came in 1928 when Fleet Problem VIII saw a successful attack by carrier aircraft on Pearl Harbour: the dawn attack was a complete surprise.(36) “Dive-bombing, introduced in the mid-1920’s, had revolutionary implications: for the first time aircraft could reliably hit rapidly moving targets such as warships. The dive-bomber could not build up enough speed in diving for its bombs to penetrate thick deck armour, so it could not be expected to destroy capital ships. It could, however, wreck a carrier’s flight deck and so disable it.(37) With this new ability, keeping the carrier as part of the battle line made no sense, nor could the carriers function as depot ships for the float planes carried by battleships and cruisers (thus Langley’s catapult was removed in 1928). The primary objective was to find and destroy the enemy’s carriers, then attack his ships and bases. Carriers required escorts to deal with cruisers and submarines and scout planes with long range to ensure (in the days before radar) that they found the enemy carriers first. War games had suggested and fleet exercises confirmed, that whoever struck first at an enemy’s carriers won the engagement (38). Thus tiny Langley, could, in theory, destroy much larger adversaries if she got in the first punch. (pictures 41, 42, 43, 44, and 45)

As an experimental ship (picture 46 above: note the autogyro), Langley was an outstanding success and many of the practices taking place today on the huge CVN’s of the U.S. Navy can be traced back directly to ‘this poor comic ship’. As new, larger carriers joined the fleet, Langley with her slow speed and small size was due for replacement. She was taken in hand and converted once again, this time emerging in 1937 as AV-3, a seaplane tender. The forward third of her flight deck was cut away to create a seaplane handling area and she was assigned to Aircraft Scouting Force and found herself at many Pacific bases. She spent part of 1939 in the Atlantic and then took up residence at Cavite in the Philippines (pictures 47, 48 and 49). She was lost off the coast of Java on February 27, 1942 to Japanese aircraft: 16 of her crew perished. (39)(picture 50)

As has been the case with all these articles, Langley is represented in 1:1250 scale – Neptun 1318 shows Langley as she was in 1930. (40) And Taubman plans service has plans for a radio-controlled Langley in 1:144 scale while plans in 1:192 can be purchased from the Floating Drydock, again showing the ship as she was in 1930. Like the British carriers described previously, there are no scale plastic kits of Langley: unlike the British subjects, there are more than one resin kit available. Loose Cannon Productions makes a 1:700 version of the Langley (41) (picture 51, above) and also a 1:700 model of the Langley as a seaplane tender. Iron Shipwrights produces a 1:350 resin kit (42) which has a laser-cut wood flight deck and a large number of photo-etched parts, particularly the girders supporting the flight deck.(picture 52). As I write this article (late March, 2010) there is a gentleman who is building a 1:96 radio-control model of the Langley. His build is described on the Warship Models Underway website ‘Build Board’. (43) His method of defining Langley’s hull plating is very unique and effective. But perhaps the finest model of the Langley is one that you and I cannot buy: it is the model donated by Commander Josiah “Cy” Kirby, USNR (Ret) to the National Museum of Naval Aviation (44). Pictures of this model close out this article (pictures 53-60). Next: IJN Hosho

1. Preston, A., Aircraft Carriers, p.25 2. Idem 3. Pawlowski, G., Flat Tops and Fledglings, p. 17. The second conversion was to have provided the fleet with a training carrier. Interestingly, the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Benson, was opposed, favouring a seaplane carrier instead. His opposition was over-ruled by the then Secretary of the Navy and the Jupiter conversion was approved. 4. IJN Shinano and the USN’s Midway class were the first carriers to be larger than Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3). 5. Preston, op. cit., p.25 No doubt Goodall was aware of Hermes’ limitations. Interestingly, the design characteristics of the earliest American studies included a double island, one to port and one to starboard that had been part of Hermes’ original design. 6. Stern, R., The Lexington Class Carriers, pp.24-26 The 6 Nov.1920 proposal was 25,000 tons, 660’x69’x25’draught with a flush deck, two elevators, 30kts speed with 16x6”guns and 72 aircraft (2/3’s dismantled); by Feb.1921 the figures were 35,000 tons, 800’ length, 34kts and 12x6” plus 12x5”guns; by May 1921 the design had grown to 850’x94’x30’ moving at 34 kts. With 16x6” and 12x5” armament: this design included an island on the starboard side. 7. Samuel Pierpont Langley was an early aviation pioneer. AC-3 Jupiter was re-named and re-designated as USS Langley, CV-1, on April 21, 1920. 8. Mitchell’s career certainly was dramatic but the USAF was not created until 1947 (and immediately was embroiled in ‘turf wars’ with the USN concerning the value of aircraft carriers vs. fleets of long-range nuclear bombers). It is arguable that Mitchell’s actions delayed rather than enhanced the chances for a separate air service being created. 9. Stern, op. cit., p. 22 The idea of only one type of aircraft on any given aircraft carrier was British but abandoned by the early 1920’s. And, of course, the Royal Air Force was in control of British naval aviation when Mitchell made his April, 1920, proposal. 10. Ibid, p.13. This author writes that the conversion of two battle cruisers then building into the carriers USS Lexington CV-2 and USS Saratoga CV-3, authorized July 1922, was a “sop to both Mitchell and the Navy”. It wasn’t much of a comfort for Mitchell. He still believed that land-based bombers would dominate future warfare. He met Douhet in 1924 and this meeting only re-inforced his views. The book he wrote on air power in 1925 saw no future for the aircraft carrier: in this book he predicted that Japan would bomb Pearl Harbour but he said it would be done with aircraft based on islands, not from the decks of ships. 11. www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Air_Power/early-navy/AP13.htm Interestingly, for the last half century commanders of United States Navy aircraft carriers must be pilots, having commanded squadrons and air wings, and learning seamanship by commanding auxiliary vessels before being given command of a carrier. 12. Stern, op. cit., p.16 13. Moffett was 52 years old at the time. 14. www.militarymuseum.org/Reeves.html 15. Naval aviation in the United States in 1925 also included balloons and dirigibles, a topic for a future article. 16. Turbine-electric drives had two advantages: one was an instant shift into reverse by switching polarity and another was a smaller crew, thus a less expensive ship. 17. Pawlowski, op. cit., p.17 18. Preston, op. cit., p.27 19. Friedman, U.S.Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History, p.36 20. www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/cv-1.htm 21. idem 22. Friedman, op. cit., p.36 23. Chevalier was a very popular officer who was Officer in Charge of the Aviation Detachment when Langley was commissioned. He died in a plane accident at Norfolk three weeks after making the first landing on Langley. www.destroyerhistory.org/fletcher_class/usschevalier He is remembered by USS Chevalier DD-451 and USS Chevalier DD-805 24. Pawlowski, op. cit., p.20 25. Stern, op.cit., p.113 26. The History of United States Aircraft Carriers, video, Pt.1 27. Stern,op. cit., pp.117,119 28. Landing Signals Officer. The flags were replaced with ping-pong paddles (the fabric of the flags would often be blown to curl around the sticks and no longer be visible). And while the LSO was ‘adopted’, one feature of the ship was lost. Picture 32 shows the stern of Langley and the search lights are on top of a structure that originally held homing pigeons for sending messages (radio sets often broke down). The bird coop was converted into the Executive Officer’s Quarters, presumably after the bird poop was cleaned out. 29. Pearl Harbour did not ‘officially’ become the main base for the U.S. Pacific Fleet (main in the sense that it was the homeport for the major units of the fleet) until 1940, the same year that the yellow wings of USN aircraft were replaced with grey. Both these moves were interpreted by the Japanese as hostile but it had the effect of making a strike on the USN Pacific Fleet much easier than if the major units were still ‘home-ported’ in San Diego or San Francisco. 30. “Another Milestone for Carrier Aviation” by Hill Goodspeed and Tom Wildenberg. As was the case with Langley and every British carrier so far detailed in these articles, the conversions were over-time and over-budget. Some things never change, even 90 years later. 31. Friedman, op. cit., p. 11 32. Perhaps this is where the nickname “Bull” came from. Certainly, with his lean frame and long face and nose, Reeves did not have ‘bull-like’ features. 33. “Admiral Joseph Mason “Bull” Reeves USN (1872-1948)” by Mark Denger and Norman Marshall, California Center for Military History, p.3 34. Friedman, N., British Carrier Aviation: the Evolution of the Ships and their Aircraft, p.19 35. “Admiral Joseph......” p.3 36. Reeves’ greatest triumph would be his role in Fleet Problem IX, to be detailed in a later article. And Pearl Harbour would be successfully attacked in two further Fleet Problem exercises in the 1930’s. 37. Friedman, U.S.Carriers...., p.11 38. No doubt the games and exercises were designed with the Japanese fleet as the adversary since the Japanese, like the Americans, did not armour their flight decks. Attacking British carriers would have been a very different undertaking. 39. www.chinfo.navy.mil/navpalib/ships/carriers/history “A Brief History of U.S.Carriers” 40. Montford Metal Miniatures (www.montfordmodels.com) also has a metal Langley – MM157 KP 41. A review of this kit can be found at www.ipmsusa2.org/review/Kits/Ships/loosecannon_700_langley/loosecannon_700_langley.htm 42. to be found at http://ironshipwrights.com 43. www.wmunderway.8m.com/ 44. Commander Kirby also donated a model of USS Lexington, CV-2, referenced in a future article Bibliography: Aerospace Power Journal, summer 2001, “In Search of a 21st century Air Leadership model” Friedman, Norman, British Carrier Aviation: the Evolution of the Ships and their Aircraft, Conway Maritime Press, 1988 ______________, U.S.Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History, United States Naval Institute, 1983 Pawlowski, Gareth L., Flat Tops and Fledglings, Castle Books, 1971 Preston, Anthony, Aircraft Carriers, Galahad Books, 1979 Stern, Robert C., The Lexington Class Carriers, Arms and Armour Press, 1993 The History of United States Aircraft Carriers, - a 13-part video series originally produced in England www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Air_Power/early-navy/AP13.htm www.chinfor.navy.mil/navpalib/ships/carriers/history “A Brief History of U.S. Carriers” www.destroyerhistory.org/fletcher_class/usschevalier “Godfrey de Courcelles Chevalier” www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/cv-1.htm « CV-1 Langley » www.history.navy.mil/nan/2000/may-june/milestone.htm “Another Milestone for Carrier Aviation” by Hill Goodspeed and Tom Wildenberg www.militarymuseum.org/Reeves.html “Admiral Joseph Mason “Bull” Reeves, USN (1872-1948)” by Mark J. Denger and Norman S. Marshall, California Center for Military History

Main Picture: USN Langley CV-1 Last Picture: USN Langley with USS Cole Picture 1. HMS Argus ----Naval Historical Center (NHC) photo # NH 42235 Picture 2. HMS Hermes --- Ships of the World; History of British Aircraft Carriers p.41 Picture 3. HMS Eagle ---- Ships of the World; History of British Aircraft Carriers p.36 Picture 4. United States Navy War College, USN, public domain; this is the original building completed in 1882: it is now the War College Museum Picture 5. USS Jupiter –USN Picture 6. US Battle cruisers NHC 41961 A painting by Louise Learned, 1922 Picture 7. USS Milwaukee CL-5 USN Picture 8. USS Von Steuben NHC, photo# NH42418. Originally this ship was the Norddeutscher Llyod liner SS Kronprinz Wilhelm; commissioned in the Imperial German navy, Aug.1914; interned at Portsmouth, Virginia, April 1915; seized by the U.S. government 6 April, 1917 and renamed Von Steuben serving as a troop transport (ID-3017) Picture 9. USS Agamemnon NHC, photo # NH 98558. Originally the liner Kaiser Wilhelm II; commandeered by the USN in 1917 and re-named Agamemnon: used as a troop transport ID-3004 Picture 10: USS Leviathan NHC, photo # NH 51392 . A huge vessel, 950x100x37, she displaced 54,000 tons. Originally the German liner Vaterland, she was completed in 1914 but was interned when the war began and seized in 1917. Until the arrival of the USS Midway in 1945 she was the largest ship ever operated by the U.S.Navy (ID-1326). After WWI she reverted back to commercial service. Picture 11: Billy Mitchell, public domain Picture 12. USS Alabama NHC photo# NH 57483 Picture 13. U.S. government, public domain Picture 14. Cartoon, NASA Museum photo; public domain Picture 15. William Moffett USN Picture 16. USS Texas, BB-35 USN Picture 17. Langley Museum of Naval Aviation (MNA) 488.010.022 Picture 18. Langley Navsource (NS) 020110 Picture 19. Insignia USN Picture 20. Langley NHC photo # NH 72927 Picture 21. Langley USN Picture 22. Diagram of Langley NS 02-020129 Picture 23. Langley- 1923 MNA 1996 488.010.005 Picture 24. Langley NHC photo # NH 81279 Picture 25. Langley National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 80-G-185887 Picture 26. Langley NHC photo # NH 47024 Picture 27. Langley NHC photo # NH 93178 Picture 28. Langley Navsource 020138 Picture 29. Langley NHC photo # NH 63545 Picture 30. Langley USN Picture 31. Kenneth Whiting USN Picture 32. Langley NARA Picture 33. MNA 488.010.003 1923 Picture 34. NARA 80-G-460108 Picture 35. Curtis F6C-1 USN Picture 36. Langley NS 013916a Picture 37. Reeves cover of Time Magazine, June 4 1934 Picture 38. Langley USN Picture 39. Langley NARA 80-G-42475 Picture 40. Moffett-Reeves NHC photo # NH 81154t Picture 41. Langley-1928 MNA 488.001.004 Picture 42. NARA 80-G-185195 Picture 43. Norfolk Shipyard Picture 44. USN 9106-5-51 Picture 45. MNA 996.488.010.038 - 1934 Picture 46. Autogyro on Langley USN Picture 47. Langley as AV-3 1938 USN Picture 48. Langley as AV-3 USN Picture 49. Langley as AV-3 USN Picture 50. Langley down USN Picture 51. Loose Cannon kit Picture 52. Iron Shipwrights model Pictures 53-60. model, Naval Aviation Museum, Pensacola, Florida

Photos and text © 2010 by Dan Linton July 16, 2010 |