AircraftProfilePrints.com - Museum Quality Custom Airctaft Profile Prints

France, traditionally a land power, has nevertheless had a navy for at least the last five centuries. At times, the French fleet could compete with any other in Europe (1) and in other eras it was definitely second-class. (2) Not able or willing to compete fully in the dreadnought race between Britain and Germany before WWI, the French fleet was definitely second class and , having contributed little to the ultimate victory, was in no position to make demands on a French society bled white by the war. (3) Prior to WWI, Italy as a member of the Central Powers would naturally be opposed to France in the Mediterranean, but Italy had little industrial capacity to build a modern navy, thus there was little pressure on France for a major naval build-up. After the war, France was in no position to compete in the race initiated by Britain, the United States, and Japan and welcomed the Washington Conference and the ‘Battleship Holiday’ it created. As one of the signatories to the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, France was allowed a navy 1/3 the size of the British and American fleets. In terms of aircraft carriers, France was allowed 45,000 tons standard (4) and in April, 1922, began the conversion of a Normandie-class battleship. This would become the Béarn, the only aircraft carrier France would have between the wars.

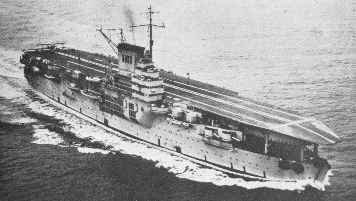

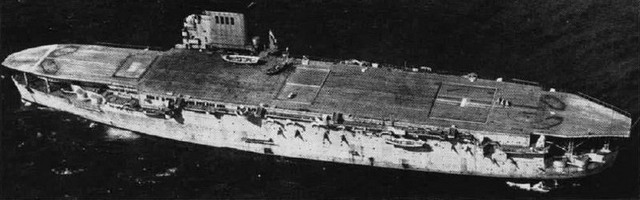

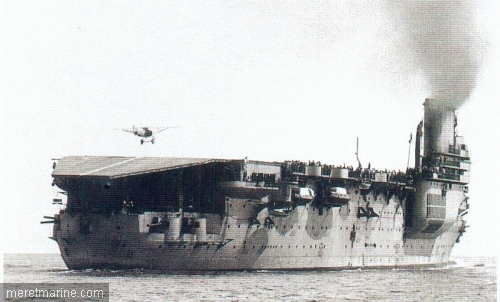

Béarn (5) was named after an ancient French province as were her sister ships when laid down originally as battleships: the name was not changed when it was converted to an aircraft carrier. She was built with the assistance of the Royal Navy which made details of the conversion of HMS Eagle available to France. (6) As can be seen in picture 1 above, many features were shared between Eagle and Béarn. The take-off deck was tapered to the front and also was sloped downward. (pictures 2 and 3)There was a starboard island with a funnel incorporated within it, offset from the flight deck on its own sponson. (pictures 4 and 5) And, coming from a battleship hull, she could only make 21kts, a speed slow enough to negatively impact air operations, particularly as aircraft became heavier. But Béarn had a number of unique features. The first was a special ventilating system that added cold air to dilute the hot funnel gases, to reduce air turbulence over the flight deck. (7) This system was enhanced in the 1930’s with more vents added to the smokestack. (picture 4) Béarn had three elevators, their outlines are easy to see in picture 1 above, but they were quite different from those used in any other navy. At the flight deck level, two huge doors opened up when the elevator platform brought up an aircraft. Picture 6 shows the middle elevator open and one can just make out the aft elevator also raised up with the hinged doors upright. Picture 7 shows only the middle elevator at the flight deck level and the hinged doors raised up. The advantage of this system was that the well for the elevator was not useless space: the platform was part of the floor of the hangar deck when lowered and the hinged doors were part of the flight deck. These doors were not strong enough to regularly park aircraft on them (and besides, the French followed British practice in not having a ‘deck park’) and would likely have been a weak point during any attack on the ship – nevertheless, it was a solution to the problem of limited hangar space. (picture 8 – note the transverse wires: I could not find any evidence that Béarn ever had the longitudinal system that British used for a decade) Béarn had two hangars: the upper one was for the 40 aircraft of the airwing, and the lower one was for workshops and spare aircraft. (8) The forward elevator gave access to the lower hangar by a system similar to that which would be used by the Japanese – a double-decked elevator, seen in picture 39 near the end of this article. The hull was laid down early in 1914 but construction was suspended during the war. The incomplete hull was launched in 1920 and would have been scrapped, as were her sisters, but she was chosen for conversion into a carrier. The conversion took a long time, the French navy requesting assistance from the British, and she was not commissioned until May, 1927. (pictures 9, 10, 11, and 12) Béarn, as the only carrier in the Marine Nationale, could not help but be considered ‘experimental’ since there were to be no other carriers authorized or even designed in France until the late 1930’s. This meant that exercises that Béarn would participate in would have little relevance to any projected conflict.

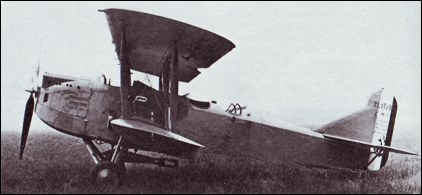

Béarn’s status was a function in part, interestingly enough, of Italian attitudes. Italy, by the Washington Naval Treaty, was allowed a navy as large as France but the rise of Mussolini to power created an interesting dynamic. Convinced of the wisdom of Douhet’s theories of the role of air power in future wars, Mussolini declared that Italy itself was an “unsinkable aircraft carrier”; that all air activities should be controlled by a single air service (9); and that battleships were of more value than aircraft carriers. (10) France was expected to counter Italy in the Western Mediterranean (most of France’s ships were based at Toulon, Oran, or Mers-el-Kébir) and without the challenge posed by mobile Italian carriers, there was no pressure to improve upon Béarn. And with only a single carrier, there was little incentive for any aircraft manufacturer to ‘push the envelope’ and develop a superior machine, since the market was so very small. Nevertheless, one manufacturer, Levasseur, produced a number of designs that found their way onto the decks of Béarn and Commandant Teste. The Levasseur PL-7 (picture 13 above), and the Levasseur PL-101 (picture 14) flew from Béarn while Levasseur’s PL-15 (pictures 15 and 16) were based on Commandant Teste, a vessel we will make reference to in a later paragraph. The Dewoitine D.376 (the folding wing version of the D.373/D.371) flew from Béarn (pictures 17, 18 and 19). The last aircraft design for a carrier plane for Béarn (and two new carriers ordered in 1938) was the Loire-Nieuport LN41 or 401, a gull-winged dive bomber.(11) It was to have been ready for squadron service in 1940 but the initial models were very underpowered and those few that were thrown into combat suffered severely and with the fall of France the project was no longer pursued.(picture 20) And by the time of the Fall of France in June, 1940, the Béarn was no longer available to the French government.

Between the commissioning of Béarn, and the authorizing of new carriers in 1938, the French Navy toyed with the idea of a hybrid battlecruiser-carrier, a ship with 8 12” guns and a catapult deck for eight aircraft. Converting the old Duquesne-class heavy cruisers into carriers was proposed but many officers insisted that at least one large gun turret be retained, thus the weakness of all hybrid designs doomed their acceptance in the French Navy as they had in the world’s other major fleets. A carrier the size of Béarn could be accommodated by France’s tonnage allowance by Treaty, but the Maginot Line took up much of France’s military budget in the 1920’s and 1930’s: a second carrier had no priority status anywhere in French government or military circles. And only minor modifications were made to Béarn during these years. (pictures 21, 22, and 23) and like her contemporaries in other navies, even the guns in barbettes near the water were kept. (picture 24) Interestingly enough, however, one aviation vessel was built for the Marine Nationale in this time period. The Commandant Teste was a seaplane tender designed to be as large as possible but still fit under the 10,000 ton Treaty limit, thus it would not count against France’s allowable carrier tonnage. It was named for Paul Teste, the pilot who made the first landing on Béarn. (12) It would be a mobile aviation base; it could service seaplanes from other ships; and it was expected to launch attacks as it was large enough to carry up to 26 seaplanes, using four catapults to launch them. At 167m x 27m x 6.7m (548’ x 88’ x 22’) Commandant Teste was almost as large as a carrier and with its high profile, and heavy equipment so far from the waterline, a special arrangement of lateral tanks allowed in water on one side or the other to help dampen the ship’s roll. It was successful but difficult to maintain. (picture 25) Commandant Teste could make 21 kts. It shipped 12 100mm (3.9”) guns and 8 37mm (1.5”) A/A guns. The hangar was three decks high and was 80m x 26.5m (262’ x 86’) and was divided in two by the exhaust uptakes. Planes were moved on trolleys: once on the quarterdeck wings would be unfolded and then cranes (there were 5 on the ship) would lower the aircraft into the sea. Smaller aircraft could be lifted through hatches 15m x 7m (49’ x 22’)in the roof of the hangar, and then placed on one of the four catapults and be sent on their way (these catapults can be seen clearly in picture 26). In service in 1932, the ship was based at Oran and Toulon for service in the Mediterranean. (13)

Béarn, obsolete by the time WWII arrived, did not suffer the same fate as some of her contemporaries in obsolescence – HMS Eagle, HMS Hermes, USS Langley – but survived the war as did HMS Argus and IJN Hosho. To be used only as an aircraft transport, the French government by May of 1940 was desperate and was using the carrier to train pilots flying Vought SB2U Vindicators (picture 27)which had been recently purchased (although the planes themselves were shore-based and not assigned to the ship). Near the end that month, Béarn was loaded with gold bullion from the Bank of France and sailed to Halifax, Canada. She then went to the U.S. east coast to load Curtiss H-75’s, SBC Helldivers, and Brewster Buffaloes ordered earlier by the French and Belgian governments. Loaded, her return trip to France was interrupted by news of the armistice with Germany, and the ship travelled to Martinique and unloaded the aircraft. The U.S. Government was very concerned for a time that the ship might be taken over by the Germans, but in fact Béarn and other French vessels at Martinique joined the Allies. Béarn spent the war as an aircraft transport (pictures 28-31) and continued in this role during the early stage of the Indochina War. By 1948 she was a training ship again and then a submarine tender. She was scrapped in 1967, having outlasted all her contemporaries. (14) In August 1939 Commandant Teste embarked six Loire 130’s (picture 32) and eight Latécoère 298’s (picture 33) and sailed for Oran. She was only lightly damaged in the British attack on Mers-el-Kébir, July 3, 1940 and later sailed to Toulon. She was scuttled 27 November, 1942 but refloated 1 May, 1943. Captured by the Germans in September 1943, she was sunk again 19 August 1944 by Allied bombers. Raised yet again in February 1945, it was felt she was repairable but that idea was dropped and she was scrapped in 1950. Thus France, the fourth country to complete an aircraft carrier, arrived at the end of World War II with no effective ships, air crews, or experience in operating naval air power. Experience would be gained through the loan or purchase of surplus carriers from the British and Americans and the purchase of mostly American aircraft. The war in Indochina saw the French Navy gain the necessary experience and by the time that new modern ships, Clemenceau and Foch, were ready in the early 1960’s they became effective units almost immediately and France is the only country besides the United States to have had CTOL (conventional take-off and landing) carriers in the fleet for the entire half-century since the early 1960’s.

Both these ships are available in 1:1250 metal offerings but there are no kits in plastic for either. In resin, in 1:700 scale, H-P Models in Germany offers both Béarn (picture 34 above)and Commandant Teste: each kit comes with 12 aircraft. In 1:400, the preferred scale in France (Heller’s plastic kits of modern warships are all in 1:400) L’Arsenal has produced an excellent kit of Béarn.(picture 35) This is a ‘mixed-media’ kit – almost 80 pieces are styrene, over 100 are resin, and the kit comes with photo-etch frets. Steve Backer’s review of this kit (pictures 36 and 37), found on the Steel Navy website, is well worth the read. Picture 38, which helps clarify some issues in the dates of different modifications, also comes from that website. Picture 39 shows the excellent L’Arsenal model produced by Loïc Blouin and shown, along with many more pictures, on the Model Warships website for Nov.16, 2010.Finally, for those interested in scratch-building, Taubman Plans has two offerings for Béarn, a 1:144 scale suitable for radio-control; and a smaller 1:200 plan. There is also from Taubman, a 1:200 scale plan for Commandant Teste. Next: HMS Glorious and HMS Courageous

1.The 1660-1690’s saw European navies struggling for dominance among the Dutch, the British, and the French. 2. The highwater mark of la marine française was undoubtedly during the War of the American Revolution: Le Compte de Grasse’s successful closing of Chesapeake Bay permitted Washington’s and Rochambeau’s victory at Yorktown. 3. Proportionately, France suffered far more than any other combatant in the Great War, in terms of deaths and casualties as a percentage of its total population; and in destruction of industrial capacity as the Western Front cut across north-eastern France, the industrial heart of the country at that time. 4. One source quotes 60,000 tons 5. Unlike many navies, there are no acronyms or initials (such as HMS or IJN or USS) placed before the names of ships of La Marine Nationale. 6. Preston, Aircraft Carriers, p.42 7. Idem 8. Idem 9. As was the case in Britain with the RAF. Mussolini’s wish became law and it was not rescinded until 1985, allowing the Marina Militaria Italiana to own and operate its own Harriers and Sea Kings from its new carrier, the Giuseppe Garibaldi. 10. In the 1930’s the Italian navy modernized old battleships and built new ones of modern design: unfortunately they were often attacked by their own air force and thus red and white stripes had to be painted on the forecastles of these major units to give warning to friendly aircraft. Level bombing of moving targets proved to be absolutely useless against ships, a fact that still did not prevent embarrassment for some Italian admirals. 11. ‘Dive-bombing’ – originally termed ‘glide-bombing’ in English – was first developed by the l’Armée de l’Air in 1923. As the years progressed, and the accuracy of this technique was shown to be excellent even against moving targets, the angle of attack became steeper and steeper and the strength of the wings, and thus the weight of the aircraft, had to be constantly upgraded, and this meant better and better engines. 12. Paul Teste died soon after, a pattern that would be repeated by Godfrey de Chevalier, first to land on USS Langley, but who died in an aircraft accident three weeks later. 13. Jordan, “Aircraft Transport Commandant Teste” in Warship 2002-2003, pp.26-36 14. Ireland, Aircraft Carriers of the World, p.124

Chesneau, R., Aircraft Carries of the World, Arms and Armour Press, 1986 Ireland, Bernard, Aircraft Carriers of the World, 2007, Jordan, John, “Aircraft Transport Commandant Teste” in Warship 2002-2003, Conway Maritime Press, pp.26-36 Preston, Anthony, Aircraft Carriers, Gallahad Books, 1979

Main Picture: French Navy, public domain Last Picture: Mer et marine.com website Picture 1: French Navy, public domain Picture 2: French Navy, public domain Picture 3: French Navy, public domain Picture 4: www.hazegrey.com Picture 5: www.vignette.net Picture 5: French Navy, public domain Picture 6: French Navy, public domain Picture 7: French Navy, public domain Picture 8: French Navy, public domain Picture 9: from a postcard, public domain Picture 10: Chesneau, R., Aircraft Carriers of the World Picture 11: French Navy, public domain Picture 12: www.vignette.net Picture 13: www.aviastar.net Picture 14: www.dauntless.soft.com Picture 15: www.aviastar.net Picture 16: www.netmarine.com Picture 17: French Navy, public domain Picture 18: www.airwar.ru Picture 19: box art Picture 20: box art Picture 21: www.meretmarine.net Picture 22: Chesneau, R., Aircraft Carriers of the World Picture 23: French Navy, public domain Picture 24: www.vignette.net Picture 25: French Navy, public domain Picture 26: French Navy, public domain Picture 27: unknown source, 1937 Picture 28: USN, public domain Picture 29: USN, public domain Picture 30: www.digilander.libero.it Picture 31: USN, public domain Picture 32: model, unknown source Picture 33: www.meretmarine.net Picture 34: H-P models; box art Picture 35: L’Arsenal models; box art Picture 36: www.steelnavy.com Picture 37: www.steelnavy.com Picture 38: www.steelnavy.com Picture 39: model produced by Loïc Blouin; found on www.modelwarships.com Nov.16, 2010

Photos and text © 2010 by Dan Linton December 13, 2010 |